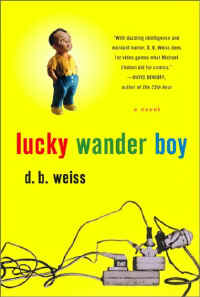

You Feeling Lucky, Punk? "Lucky Wander Boy" Offers a Mainstream Meditation on Videogames and the Nature of the Quest J. R. R. Tolkien, who knew a thing or two about The Quest as a literary tent pole, once observed that "Not all who wander are lost." Author D. B. Weiss gives us a living, breathing testament to the wisdom of that observation in his compelling, creative novel "Lucky Wander Boy". Wrapping himself around a youthful obsession with videogames while conjuring a coin-op incarnation of his protagonist's personal Grail, the author takes us on a literary walkabout that wanders but is quite clear as to where it's going.  The book is both a tribute to the videogames of the late 70s and early 80s and the saga of how a young man throws away his life (though true to Weiss' coin-op motif, he gets several replays) in a search for grandiose meaning where it never existed is must-read material for anyone who loves classic electronic games – i.e., anyone who ever visits this site. It may not be a perfect novel, but no one has ever offered such scintillating insights into its chosen subject matter. The book is both a tribute to the videogames of the late 70s and early 80s and the saga of how a young man throws away his life (though true to Weiss' coin-op motif, he gets several replays) in a search for grandiose meaning where it never existed is must-read material for anyone who loves classic electronic games – i.e., anyone who ever visits this site. It may not be a perfect novel, but no one has ever offered such scintillating insights into its chosen subject matter.

Protagonist Adam Pennyman is bearing down on age 30 without any special skills (attributes?) or goals, his life a generic platform game. Then he learns about the MAME phenomenon and reconnects with the videogames he played as a boy. This leads him to start a book which he titles "The Catalogue of Obscure Entertainments." In most cases, the entertainments aren't exactly obscure (he opens with a lucid and absolutely incandescent rumination on Pac-Man, for example). Adam soon finds himself obsessed by a genuine obscurity, however, in the form of the eponymous coin-op and its curious creator. Lucky Wander Boy (the made-up game, not the book about the made-up game) is basically the Seinfeld of golden age gaming – a coin-op that was quite literally about nothing. The game is, in fact, so pointedly vague and pointless that it becomes the perfect canvas on which Pennyman can project all his weird intellectual fetishes (including his neurotic fascination with an apparently apocryphal book entitled "Leng Tch'e" whose protagonist is a woman subjected to the legendary Death of a Thousand Cuts). The mythical LWB is presented as the creation of Araki Itachi, a female Japanese game designer who once worked at Nintendo (female game designers in the Japanese coin-op milieu of the 80s were about as common as dwarfs in the NBA, but Weiss is almost deft enough to pull this one off). Then, through one of those strange coincidences that could easily be confused with the ring of destiny, Adam lucks into a gig with a (pre-collapse) dotcom-driven content house that just happens to own the movie rights to LWB. From that point on, there's no stopping Pennyman as he goes off full throttle in search of both the game – especially the metaphysical and supposedly-unattainable third level – and its creator, about whom he has developed a serious obsession. "Lucky Wander Boy" is a contemplation of the Quest as a theme in media and literature as explored through a Kabala of videogames, both classic and esoteric, and a patchwork of Eastern and Western Philosophy. Why does Lucky Wander Boy wander? Where is he going? Does it matter? Can anyone reach the third level? What did Pennyman (Penny Arcade Man?) see in this game that is the ultimate in esoteric arcadia, too boring to have ever even been produced in the real world? Why is he so driven to locate a copy and play it? And what makes him think he's the Chosen One, destined to translate this aimless coin-op into an equally desultory screenplay? Does the game even exist? Or is it the fractured collective memory of a few dozen gamers who read previews of LWB in magazines like Electronic Games and transformed their fervid awareness of the thing into a false memory of its actual existence? According to the book, the initial level of LWB sounds so commonplace that it almost could have existed. It's a milk run filled with the standard no-challenge platform game enemies who inhabit a coin-op's earliest moments and then wraps up with a formulaic battle against the Level Boss. The second level/act of LWB is sort of an existential incarnation of Manhole – or an early version of Myst, before it was beautified by painterly 3D graphics – but without anything interesting to explore! Most players who reach this level seem to abandon it on their own, bored with the lack of meaning and movement. The game's hero wanders aimlessly through this level until, as a result of luck, fate, synchronicity or pure chance, the player-character stumbles into the legendary third level, which takes both Lucky and the player places no videogame has ever gone. Pennyman seeks the purity of the classic videogames, convinced that these contests possess great power (as a boy, Pennyman became convinced that his success at Imagic's Microsurgeon was defeating the cancer in his dying grandmother's body, only to have his Intellivision break down and his granny die) and pearls of wisdom delivered via bursts of binary code. He develops a philosophical obsession with even the most seemingly trivial components of these old games (Pennyman ponders at great length the question of where Pac-Man really is during that brief instant when he is passing through the wrap-around tunnels and disappears from view). He understands instinctively that the newer, “prettier” games are infinitely less appealing, less visceral. The very crudity that was imposed on designers of the classic, abstract classic videogames, from Air-Sea Battle to Tetris, was the crucible that tempered them into masterpieces. On the other hand, Pennyman is inevitably seduced by the newer, flashier games and even becomes a slavish devote’ of that most redundant of all game genres, the 2D fighter, in the form of a Mortal Kombat clone dubbed The Eviscerator. There are some oddities and lapses, as observed in the excellent review which appears elsewhere on this site. The book is not altogether successful in its attempts to ape the non-linearity of electronic gaming quests, for example, and it occasionally gets lost in its own metaphors – or, to put it in coin-op terms, some levels are a little awkward. There are also some chronological infelicities. If Araki Itachi worked at Nintendo before founding her own game company, for example, then LWB must have appeared several years after the other games referenced in the Catalogue. In fact, author Weiss plays rather fast and loose with chronology throughout the book (I was delighted to read of Pennyman's encounter with back issues of Electronic Games magazine, but he refers to several issues from 1981 when, in fact, the first issue was dated Winter '81-'82). And Pennyman's high opinion of 2600 refuse such as Yar's Revenge and Raiders of the Lost Ark is pretty much inexplicable. Many readers will also find themselves wishing that more of the book were devoted to reprinting entries from Pennyman's "Catalogue of Obscure Entertainments." I've written literally hundreds of game reviews since 1978, but Weiss' analysis of Pac-Man takes the contemplation of video games to a level I've never even approached:

"Pac-Man is the world's first metaphysical video game. Like a black hole's event horizon, the impassable barrier of its CRT screen hides a richness we can speculate about but never experience directly. What happens in its unseen regions? Perhaps the laws that reign there are not the brutal laws of the maze. Perhaps the tunnels move through an endless Valhalla of energizer dots with no ghosts in sight, tantalizingly close, if only we could break free.

"There is a world beneath the glass that we can never know." Wow. The first novel to be written in the style of a videogame, "Lucky Wander Boy" is a bold literary experiment that will delight and intrigue anyone who truly loves electronic games. If "Lucky Wander Boy" were a coin-op, I would have been dropping tokens right through the final chapter (or chapters, in this case). The book is a little heavy, at times, but the revelation of Itachi's new venture and her reaction to Pennyman when the two finally meet is well worth the weight. And if the whole doesn't quite equal the sum of its parts, those parts are primo, indeed. |